RANCHO DE LA OSA HISTORY

EXPERIENCE CENTURIES OF HISTORY

Welcome to Arizona’s most historic ranch…

Rancho de la Osa offers a unique convergence of Native American, Spanish, Mexican, ranching, political and Hollywood history. The land La Osa stands on is home to centuries of history from its origin as indigenous tribal lands to its modern dude ranching history.

The ranch’s original adobe buildings still stand with the earliest built in 1722 by Jesuit missionaries who traveled with Father Kino. La Osa operated as a cattle ranch through the 1800s, during which the Spanish-style hacienda was constructed. The ranch first welcomed dudes in the 1920s and in its years as a dude ranch, played host to prominent guests including politicians, Hollywood actors and authors. Today, by building upon the traditions of its past, Rancho de la Osa offers an authentic western experience to its dude ranch guests in the borderlands of Southern Arizona.

PALEO-INDIAN, ARCHAIC & EARLY AGRICULTURAL PERIODS

In archaeological studies, the first evidence of humans in Arizona came from the Clovis Culture during the end of the Pleistocene Era. In Arizona, this Paleo-Indian period took place from 13,000 to 7500 BCE. Toward the end of the Pleistocene Era, nomadic groups of hunter-gatherers emerged and hunted smaller game using small projectile points, and relied upon native vegetation like mesquite and fruit from cactus, and ground the seeds using metates. Archaeologists refer to this time from 7500-2100 BCE as the Archaic Period.

Agriculture was introduced to the Southwest sometime around 2100 BCE, at the same time settlements and more permanent villages were established in the area. Trade of raw materials and exotic goods became more prominent and early ceramic technologies developed. From 300 BCE to 300 AD the site which today houses La Osa was inhabited by people from Oasisamerica, the cultural precursors to the agrarian societies that followed.

Petroglyphs found near the ranch.

PRE-COLUMBIAN ERA

Two prehistoric farming systems developed in this area. The Trincheras people built terraced fields in the desert foothills and lowlands, with high concentrations in Sonora, Mexico; and the Hohokam relied on hand-dug irrigation canals in areas with river valleys in Arizona, like the nearby Santa Cruz River.

The modern U.S.-Mexico border is the site of a transition between the Trincheras and Hohokam cultures in the late prehistoric period, from 800-1300 AD. Archaeological sites include evidence of both traditions.

From 300 onward the Hohokam culture inhabited the area around La Osa; until about 1500 when the predominant indigenous culture became Tohono O’odham and remains so to this day. The O’odham were possibly descendants of the Hohokam and were living in and farming the area when the Spanish arrived.

The Baboquivari Mountains to the north of the ranch have one of the few remaining indigenous names in Southern Arizona, coming from the Peak’s O’Odham name meaning “a neck between two heads” or “a rock drawn in at the middle.” The Peak is sacred to the O’Odham as it is considered the center of their universe and home to their creator.

The Baboquivari Mountains and sacred Baboquivari Peak.

“A few miles south of Tucson, Arizona, a might shaft of granite stands naked and alone in the desert plain like a giant sentinel guarding a portal, and warns all who pass through that his feet are planted in a land of comfort and convenience with all modern humanity’s nerve shattering annoyances. Whereas beyond to the South is intriguing mystery, the illimitable treasure of the desert in Mexico.”

SPANISH EXPLORER ERA

Jesuits and the Pimería Alta

In the mid-1500s, the area was first explored by the Spanish, who were looking for mineral wealth and with them brought cattle, horses, sheep, fruit trees and metal tools to the native populations.

Late in the 1600s, Spain worked to strengthen its claim to this region of New Spain, establishing missions and presidios, or military outposts, to create European-style communities. The Spanish named this region the Pimería Alta encompassing the border of western Arizona and Sonora, Mexico. Converting the native peoples to Christianity was among the first steps the Spanish took to assimilate the indigenous populations they encountered. Different orders of Catholic priesthoods were called into action with the Society of Jesus, or the Jesuits, being sent to the Pimería Alta with the goal to establish missions throughout the area.

Jesuit missionary Eusebio Francisco Kino first arrived to the Pimería Alta in 1687. He and his followers continued founding over 20 missions throughout the area including San Xavier del Bac and Tumacácori.

In his travels, Father Eusebio Kino arrived at the O’odham village where La Osa now stands. Later, in 1722 Jesuit priests built a mission outpost—today that building is the ranch’s Cantina. It was used for over a century as a trading post to exchange goods with indigenous tribes and as a place for traveling missionaries to rest.

In 1767, the Jesuits were expelled from New Spain after a royal decree by King Charles the III, who became convinced the well-educated Jesuits were planning to overthrow him. A different order of Catholic priests, the Franciscans—who originally were sent to New Mexico and east of the Sierra Madre—continued Spain’s mission in the area.

The historic Cantina, originally a Jesuit mission outpost built in 1722.

“About two hundred and fifty years ago the Jesuit priests had a ‘Rancheria’ on the land that is now occupied by La Osa. For years and years wandering padres, roving Indians, possibly Anza the Founder of the Port of San Francisco and a great Indian fighter, caravans with bullion from the rich mines to the South and east, and later desperados stopped at this old ranch for rest, refreshments and devilment.”

The Franciscans

The Franciscans replaced many Jesuit churches with more elaborate structures and added onto existing missions and outposts. On the land now occupied by Rancho de la Osa, Franciscan priests began building living quarters near the original mission outpost in 1768. These quarters became the origins of the ranch’s Hacienda, where the salon and office stand today.

The Cantina interior circa 1930.

CATTLE RANCHING HISTORY

The Spanish first introduced cattle to what is now the United States through Arizona. Open range ranching was a traditional practice from Andalusia and was carried on by the Spanish settlers leading to the proliferation of cattle in Mexico and this area.

In 1529, a brand book was developed and ranchers in Mexico followed the traditions of the mestas, or livestock associations, of Andalusia. A livestock association for all of New Spain followed in 1537. Spanish cattle that were able to reproduce with little mixing of modern breeds are called criollo, or “cattle of the country.” Criollo that exist in the Americas today are descended from a small number of Andalusian cattle brought by the early Spanish settlers and explorers.

Spanish and Mexican Land Grants

During the latter years of Spanish rule, settlers in the area returned to pursuits like ranching and mining. From 1790 to 1820 the missions and rancheros in the area experienced a time of relative peace. Warring tribes were abated with peace treaties through bribery and gifts, and the rancheros’ cattle herds became so numerous they began pushing into the northern frontiers of New Spain. In their time of expansion, these rancheros sought land grants from the Spanish and Mexican governments.

The land surrounding La Osa became a part of the rangelands for these rancheros and the Don Agustin Ortiz Spanish land grant of 1812 included the ranch’s acreage.

In 1848 the Mexican-American War broke out as the U.S. sought westward expansion and the borders of each country were disputed. While the war did not directly impact what is now Southern Arizona dramatically, the events to follow shaped this area and the borders that exist today.

After the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo officially ended the war, Spanish and Mexican land grant owners could seek continued ownership of their titles if they found evidence of their grant’s legality within government archives. Fraudulent claims and poor documentation stymied clarified ownership for years, and rancheros moved ahead claiming land around the state without legal documentation. The ranchlands of La Osa were among those disputed territories, inciting a scandal which sought to include the headquarters within Mexico by falsely moving the international border survey line.

In 1853 the ranch became a part of the Arizona Territory with the Gadsden Purchase. Ratified in 1854, it was a $10 million transaction for 30,000 square miles of land in what is now Southern Arizona and Southern New Mexico.

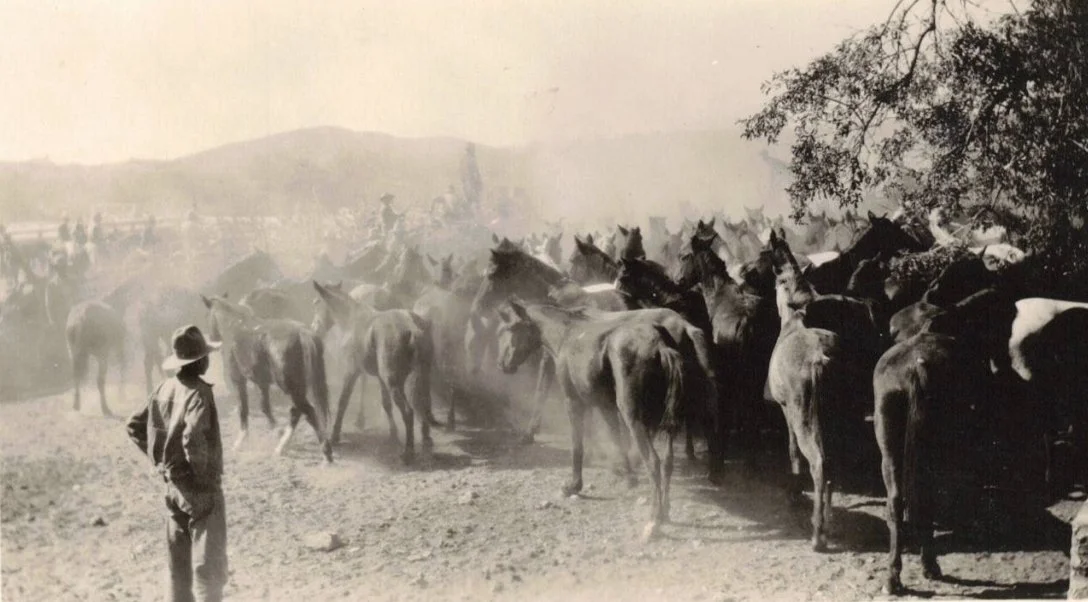

Cattle crossing the U.S.-Mexico border in Sasabe, Arizona. Cattle crossings were an entertaining event for dude ranch guests at Rancho de la Osa well into the 1940s.

The Hacienda at La Osa

In 1887 Colonel William S. Sturges of Chicago acquired ownership of La Osa. He spared no expense finishing the Spanish-style hacienda, which featured wood floors, stained-glass windows, and 10 acres of gardens. It was noted as “one of the most remarkable structures in the territory” and remained a large cattle ranch with headquarters where the ranch buildings remain today.

Haciendas were a crucial part of the Mexican economy, often established on royal land grants for mining. Cattle were initially raised for food and resources for miners, but soon became the cornerstone of the hacienda economy.

Early pioneer ranches in the United States adopted the building practices of the hacienda, in part due to the availability of adobe as a construction material with the addition of local resources like saguaro ribs and ocotillo stalks. The Spanish brought ideas of how whole towns should be planned, which were adopted into the layout of a traditional hacienda with the main house as a focal point and other ranch buildings spaced out like a small town. The hacienda at La Osa embodies these construction practices.

The La Osa name originates from a story where a Mexican vaquero roped and killed a silver tip bear and her cub near the ranch. From then on it was called La Osa Ranch. Sturges took pride in the name including a bear and three cubs on his letterheads. This story is recorded from Frederick J.M. Ronstadt, who arrived from Mexico to Tucson and was a pioneering figure in the city, as well as a cattle rancher, who purchased land that was originally part of La Osa from Sturges. He was also Linda Rondstadt’s grandfather.

The courtyard in the rear of the hacienda at La Osa.

Changes to the Desert Landscape

The grasslands of Southern Arizona were forever changed by the proliferation of cattle ranching in the area. Initially Mexican cattle did not strain the grasslands; but further increases to cattle populations beginning in the 1870s prevented native grasses from regrowing at their usual rate. In the absence of abundant grasses, mesquites and woody shrubs were able to grow, further preventing the return of grasslands. Additionally, human intervention to suppress fires and harvest hay allowed these slower growing trees and shrubs to multiply, where previously natural fires enabled fast-growing grasses to flourish.

Changes to the local flora and the addition of larger numbers of cattle caused faster erosion, changing the courses of streams and seasonal water flow, or causing some water sources to only run below ground. The arroyos and washes that are quintessential to Arizona were largely caused by the introduction of cattle to the area.

Men on the porch of the guest rooms, circa 1902.

La Osa Cattle Company

In 1901 the ranch sold to La Osa Cattle Company, where cattle operations continued well into the ranch’s dude ranching era. The cattle company changed hands several times during the turn of the century between prominent local ranchers and business owners, and cattle ranching remained a chief attraction for dudes into the mid-century.

Initially, La Osa Cattle Company was run by rancher W.D. Coberly and the Coberly family operated it for over a decade. W.D. Coberly also owned the Palo Alto Ranch among others in the Altar Valley. In 1903, William B. Coberly, the son of W.D., came to Arizona to manage the La Osa Cattle Company. It was described to be “splendidly equipped and supplied with all of the facilities and conveniences found upon the modern cattle ranch of the present day.” W.B. Coberly ran for County Supervisor and was instrumental in the creation of a passable road from Three Points to Sasabe—critical later to the dude ranch guests that would arrive by car.

Jack Kinney and partners purchased the ranch and cattle company in 1915. Kinney also purchased multiple ranches in the area and was an influential figure in Tucson’s history, as a member of the County Board of Supervisors, and was instrumental in the creation of the Fiesta de los Vaqueros Rodeo in Tucson.

LA OSA BECOMES A GUEST RANCH

The hacienda at La Osa was constructed in the late 1880s by Colonel William S. Sturges.

Guest ranching in Arizona shaped the early tourism image of the state. Beginning largely as cattle ranches that hosted guests, they morphed into ranches catered to tourists in the image of the American Southwest, offering horseback riding, working ranch experiences and, oftentimes, resort-style amenities. Guest ranches around the state were at the forefront of introducing Arizona tourism to the rest of America, providing the activities and lifestyles of the West.

Arizona rose to the forefront of offering wintertime dude ranch vacations to its visitors, relative to other states in the Southwest. The emergence of dude ranching in Arizona came in the 1920s and ’30s; and more often the term “guest ranch” was used than “dude ranch,” unlike their northern counterparts.

Guests were often from the East Coast or Midwest and would typically stay for considerable amounts of time. Arizona guest ranches placed an emphasis on comfort and relaxation for guests breaking from traditions of early dude ranching in northern states but encompassing the overall trend for dude ranches of the mid-century. Arizona guest ranch advertisements often lured guests with promises of the warmth, sunshine and health benefits of the desert climate.

Hacienda de la Osa

In October 1924, John and Louisa Wetherill arrived to La Osa. Louisa Wetherill lived with her husband and children in remote trading posts among the Navajo people for over 25 years, becoming an authority on Navajo culture and speaking the language. In the 1910s and ’20s the Wetherills operated a trading post and lodge in Kayenta, Arizona, where they welcomed visitors like Theodore Roosevelt and Zane Grey. The Wetherills made trips to Mexico to investigate claims Navajo clans had migrated south in pre-Columbian times. In their travels, they found La Osa and decided it was an ideal place to house winter guests and create a dude ranch. It opened to guests as Hacienda de la Osa on Thanksgiving, 1924.

John Wetherill and Cloyd Colville leased the ranch from J.C. Kinney during the Wetherill’s time of managing it as a dude ranch.

The Wetherills drew prominent figures to Rancho de la Osa, often those who were visitors to Kayenta lodge and trading post. Zane Grey wrote four novels on the ranch, and one specifically about dude ranching: The Dude Ranger: A Western Story (1930).

Early dude ranch guests at La Osa.

Glenn Hardgrave Era

In 1927 Glenn Edwards Arthur Hardgrave, a Kansas City socialite and writer, became the owner of La Osa after her husband, Arthur Hardgrave, purchased the ranch as a birthday gift. She had been a guest in 1926, and went on to write a series of articles about her experiences at the ranch in the Kansas City Journal-Post. This included an article describing the 1929 Battle of Sasabe where the ranch was turned into a hospital to care for soldiers injured in the battle, which was an insurrection against the federal government following the Mexican Revolution.

An advertisement for Hacienda de la Osa in a 1934 issue of “Guest Ranches on Lines of Southern Pacific” reads “One of the oldest ranches in Arizona, retaining the spirit and romance of the Old West. Plenty of big game, such as mountain lion, bear, deer, wild hog, mountain sheep, nearby in Old Mexico; also deep sea fishing. Guides and camping equipment may be arranged for. Horseback and automobile trips to many interesting points in Arizona and Old Mexico.”

Glenn Hardgrave owned the ranch until the spring of 1929, but bought it again two years later, once again operating it as a guest ranch and private home. Glenn’s sister Charlie and her husband James H. Jones were hosts at the ranch from 1931 to 1933. It was sold in 1936 to Edward Dickerson Jenkins.

“I discovered what a Westerner calls a gentle horse. If he doesn’t kill you, he’s gentle. If he does, he’s wild. My first morning after arriving at La Osa ranch, I asked if they had any nice, gentle horses. Was informed they had. ...

Those gentle horses were going like racers around the track, pausing long enough now and then to rear themselves on hind legs, handing out a few kicks on their way down, then giving themselves a few humps in the middle to show just how nice and gentle they were. … By remembering that once I was from Texas, and had some ancestors who were cow punchers, I was saved from total disgrace and what was infinitely worse, from the stigma of being called ‘dude.’ I climbed on Thunder, rode him and live to tell the world he is a gentle horse.”

POLITICS AND HOLLYWOOD

Lady Bird Johnson in front of the historic Cantina.

In the late 1930s, Edward Dickerson Jenkins arrived a La Osa. He was a prominent Democratic politician and syndicated ownership of the ranch in 1938 with other politicians from Washington D.C. continuing to operate it as a dude ranch, but under the name Rancho de la Osa.

The ranch closed for a few years during World War II and reopened in 1945 after Dick returned from the air corps. His twin sister, Nellie, came to help run the ranch.

Guest ranching in Arizona became its most popular in the 1940s with the largest growth of new ranches in the state. Large numbers of them were close to urban areas like Phoenix and Tucson. Horseback riding remained the main attraction for guests, but a heavier emphasis on amenities and more activities developed, especially at newly constructed ranches in the state.

Notable Guests

Dick became chairman of the Arizona Democratic Party and many prominent politicians were entertained at the ranch over the next decade including Lyndon B. Johnson, both Roosevelts and Adlai Stevenson. Jenkins told Elliot Roosevelt—son of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Eleanor Roosevelt—about the ranch, leading Eleanor to spend many Christmases at La Osa. Assistant Secretary of State William Clayton drafted the Marshall Plan in a house behind the main hacienda—now called the Clayton House—which was constructed for his use during the war while the ranch was a secluded retreat for guests from Washington.

William O. Douglas stayed at the ranch and wrote about Baboquivari Peak in 1961 in My Wilderness: East to Katahdin: “The peak has many moods. Mornings when the skies are clear it has a dazzling splendor. By noon the desert dust riding high in the heavens often casts a haze about it. Then its sharp lines are gone and it becomes softer and more remote—a bit out of focus. On a clear day it has a bluish tinge. By midafternoon, when shadows lengthen, Baboquivari seems to tower even higher in the sky. It then turns a dark purple.”

Twenty-three hollywood movies were filmed at the ranch, bringing notable actors and directors like Joan Crawford and Cesar Romero. Tom Mix brought then-extra John Wayne to La Osa and part of Hondo was filmed at the ranch.

Dick Jenkins died of a heart attack in 1956 while introducing Adlai Stevenson at a rally in Phoenix during his second run against Eisenhower. At this time Nellie, his twin sister, operated the ranch until 1962. She died 10 years later and both she and Dick are buried in the ranch’s cemetery.

“Horseback riding is the chief recreation on the ranch, and frequent picnics into Mexico or into the Baboquivari mountains are arranged. The ranch owner has obtained special permission from the government at Mexico City to allow his guests to ride south of the border where there are large tracts of unfenced land. [Jenkins] always carries the ‘Key to Mexico’ on a wooden key ring when they go riding.”

A Hardgrave-era image of the Hacienda, which was used for advertisements and postcards.

The historic courtyard at Rancho de la Osa.

The dining room at La Osa, circa 1930.

Horses in the historic retaque corrals using stacked mesquite branches.

Cowboys in the pasture at Hacienda de la Osa.

Dude ranch guests, including actor César Romero (third from left), on a snow day.

Cattle in the retaque corrals.

The Hacienda courtyard in the 1920s.

A historic postcard from La Osa.

Horses in the pasture at La Osa.

One of the salons inside the Hacienda.

Two riders pose in front of the Hacienda's adobe walls.

The corrals at Hacienda de la Osa.

The dining room, circa 1940s.

Riders pose in the retaque corrals.

Riders on a cattle drive.

A cattle dip tank at the border crossing.

A group of riders outside of the Hacienda in the 1930s.

MODERN HISTORY

From the 1960s to 1982, the ranch’s ownership changed hands, operating as a cattle ranch or guest ranch. In 1982, Bill Davies bought the guest ranch and the rest of the ranch’s acreage became the Buenos Aires National Wildlife Refuge in 1985 under the Endangered Species Act to reintroduce the endangered Masked Bobwhite Quail into the wild.

The ranch was renovated and reopened to guests and run as a dude ranch by the Davies and then Veronica and Richard Schultz until 2014.

In the spring of 2017, the ranch opened once again to dude ranch guests.

Conservation Efforts

Rancho de la Osa is located adjacent to the 117,464-acre Buenos Aires Wildlife Refuge. Known for its high desert grasslands, it also features riparian areas with seasonal marshlands, meadows, cottonwoods and mesquite groves, providing rich habitat for a large variety of wildlife. It’s a birder’s paradise with a tremendous array of species including different orioles, tanagers, herons, ducks and hawks. Though bears and Mexican gray wolves are no longer in the area, mammals like pronghorn, mule deer, mountain lions, and javelinas still roam. There have even been sightings of the elusive jaguar.